Mapping the City closes this weekend which perhaps makes it a little strange to be posting this review. I’ll admit bad timing and poor organisation has played a part in this, but it reminds me of one of the things we agreed upon at our writers meetings for ArtSelector: that we were not writing reviews primarily to recommend that readers visit exhibitions, or indeed, not to bother. (Although in this case I absolutely do recommend that if by some chance you can pop along to Somerset House today or tomorrow, you should. Galleries are romantic right?) Our reviews are not supposed to be an extended exhibition listings. We’re not here to tell you what’s hot and what’s not. We hope to create something else by writing about exhibitions, something that sits alongside them. A written journey that, perhaps, is allowed to wander elsewhere, away from the exhibition, on a tangent, which is what I am doing with this review in a totally self-serving way.

Which, conversely, actually brings me back to maps; navigational tools that summarise, provide information and to an extent, conquer. Mapping is a military reconnaissance mission and a map is a logistical system and potentially, a weapon. The map, the plan, is a birds-eye-view of the city, while the person navigating its innards has a very different, rather more messy experience. Even attempting to trace that journey is just one personal story among the crushing throngs of lives that pass each other everyday. As the attempts of the late twentieth-century ‘psychogeographers’ showed—to whom, not unsurprisingly, many of the exhibitors in Mapping the City owe differing degrees of inspiration—trying to systematise the ground-level experience of urban life into a scientific and objective approach is to create overly confident, artificial categorisations and silence the ongoing narrative of sleepless cities.

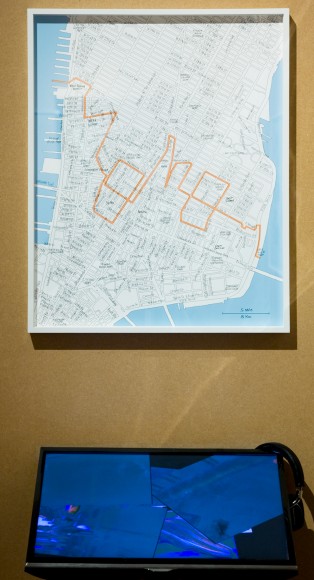

Mapping the City is made up of these subjective maps, cartographic art works by 50 street artists from around the world coding and claiming their streets, their underground catacombs, their cycling accidents, their histories and their fictions. To write a review is essentially also to create such a map. I enjoy joining the dots, navigating from work to work, artist to artist, thought to leading thought, tracking mental markers, scribbled notes, all reviewed again while sat at a keyboard and sketched into something that hopefully can be followed. The review is, in some ways like giving the reader my map of the exhibition. Not literally though—you wouldn’t want it. It’s been annotated with weird, dramatic things like “the city is a god”, “payote”, “where is Allessandria?”, “bodies, microchips, gauze”, “tagging” and “Neverware”. Because, of course, like all exhibitions, Mapping the City, has a map. Each work is numbered, running in a sequential snake down the page while a series of colour coded arrows connect piece to piece, and artist to artist by medium and or/theme. On my map, I drew another set of arrows. One runs between number 11 and number 16— 11 being The Book of Bitumen: Chapter One, 2015 and Rubble Trauma Tower, 2012-2015, by Cult of RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ and 16 being Gold Peg’s London’s Burning, 2013. A journey between a video of ritual cultists ‘breakspraying’ on layered lino, chanting hip-hop prayers with symbolic, de-soled Addidas trainers strung around their necks, to a dark, autobiographical ‘Where’s Wally?’ map of London, where witches and hell hounds laugh at green vomit spewing hipsters in Shoreditch or toast marshmallows over the head of a three-eyed, tentacled monster clutching Selfridges and Top Shop shopping bags in the hell hole that is Oxford Street. From there my scrawled line navigates to 47, Susumu Mukai’s detailed pencil drawing, Regent’s Canal, East London, 2012-2014, 2014: a map of memory, a map from maps, from drawing, notes and countless navigations. A short hop over then to 50 lands in Will Sweeneys fantastical rendition of Cabott Square, Canary Wharf, 2014 complete with a Bull god, battery farm body enslavement, skull-stacked skyscraper towers in which skeleton men do desk-work and talk on the phone, monsters that slither in the Thames, alien invasions, some truly amazing looking ‘end of the world’ parties and, of course, ceremonial blood sacrifice. I then followed Tim Head’s heady night drive through London to the work of Nug, and Nug and Pike, and the adrenalin pumped performance of the graffiti artist, and a train obsession, to the quiet, lonely Parisian catacombs where Psyckoze has been secretly at work for many years. From here the line heads back up to number 13, to Daniel Gotesson’s Rational Disorder I & II, 2014, an abstract ink and spray paint diptych that channels the psychogeographic spectre that haunts all introspective city wanderings.

So that’s my map of Mapping the City and I hope that in this case, if you get yourself down to Somerset House lickety-split, and with other reviews and exhibitions, you have fun writing, crossing-out and drawing a new map over the top.

Mapping the City is at Somerset House until 15 February 2015, in association with collaborative arts organisation A(by)P.