I only had one issue with this exhibition, excellent though it was: and that was its title. I knew that it was called “Around Drawing”, not “On Drawing”, or just plain “Drawing”, so I could readily infer that the works on display there wouldn’t all be drawings. And of course, they weren’t. What they actually had in common was not drawing as such, but evidence of the continued importance and direct relevance of the skills of draughtsmanship in current art practice.

A strong element in Rosenfeld Porcini’s curatorial approach is a sense of the continuation of the traditions and history of art, and that is certainly felt in this exhibition. Draughtsmanship was, of course, the very foundation of art training and education for hundreds of years. Drawing is the first artistic endeavour of every child, at play and at school. It was also the first skill learned, laboriously and thoroughly, by any professionally trained artist.

While most of the great art innovators of the first half of the twentieth century were exceptional in the quality of their draughtsmanship and revered that skill (Picasso and Duchamp particularly spring to mind), things began to change in the second half. Conceptualism arrived and with it came the startling assertion that technical skill was unnecessary and irrelevant to an artist. As time passed, the enfants terribles of the conceptualist avant-garde inevitably became part of the art establishment. How far this had progressed became clear in 2011 when Tracey Emin, best known for her controversial art installations, was appointed Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy, to the consternation of some who questioned her suitability for the appointment. Emin does make drawings, but that is not really the point as the aesthetic and skills of drawing as such are not part of their intention or appeal. When conceptual artists make paintings, drawings and sculptures, they frequently do not express themselves through those media, but rather on and about them. They do not continue a tradition so much as appropriate it in order to critique and subvert it; for example, in Damien Hirst’s spot and spin paintings, he relies on their lack of painterliness to make a conceptual point about the medium (one which I suspect has been lost on many of his “collectors”).

In this group exhibition, however, the importance and relevance of traditional draughtsmanship skills to significant strands of contemporary art practice are givens. It features the work of eight of Rosenfeld Porcini’s international roster of artists: Enrique Brinkmann from Spain, Lu Chao from China, Antonis Donef and Marianna Gioka from Greece, Lanfranco Quadrio and Nicola Samori from Italy, Marcel Rusu from Rumania and Eduardo Stupia from Argentina.

Two fine examples of art emphasising traditional draughtsmanship skills are Marcel Rusu’s works on paper, inspired by Georges Méliès’ 1902 silent film A Trip to the Moon (considered by many to be the first ever science fiction film). In these, he uses charcoal, pastel and acrylic in heavy and grainy monochrome tones to create drawings resembling blow-ups of old movie stills.

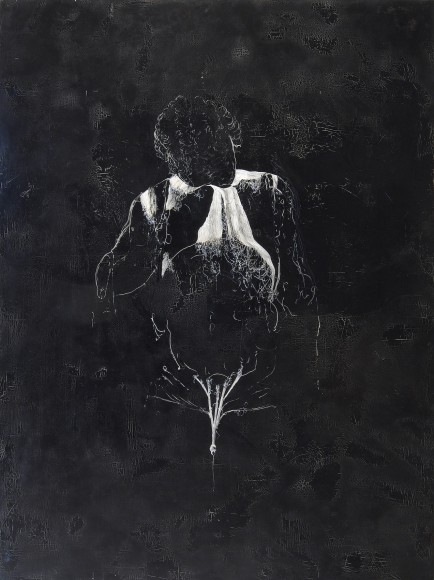

Acrylic, oil, pastel, graphite and pen on both paper and canvas are used by Lanfranco Quadrio to create powerful and dynamic images which successfully convey mood and movement. In some of the works here, he reimagines horrific scenes from the myth of Diana and Actaeon in which the huntsman Actaeon, who happens upon Diana bathing, is transformed into a stag in revenge, and is torn to pieces by his own hounds. These works echo and develop the theme of several paintings inspired by this myth over the years, most famously Titian’s The Death of Actaeon, and later in Giambattista Pittoni’s Diana and Actaeon (where the bloody action is just a background detail) and Turner’s The Death of Actaeon, with a Distant View of Montjovet, Val d’Aosta, where the landscape predominates. Here, Actaeon’s suffering and the violence of his death are emphasised in a manner reminiscent of Goya and, perhaps, Francis Bacon.

Antonis Donef uses pages taken from antiquarian books in various languages as a surface, on to which he draws fantastical figures using ink. The artist’s mark-making blends effectively and harmoniously with the yellowing pages; the synthesis of the two elements takes on the appearance of an alchemist’s cookbook or a manual for some esoteric and archaic mechanical invention.

Eduardo Stupia is a painter of powerful semi-abstract “landscapes”. Marianna Gioka also paints abstracts but these have a delicate, ethereal quality which, with their muted sepia tones, remind me of Zen symbolic figurative painting. Both artists’ working methods are clearly rooted in draughtsmanship and both use drawing materials to add surface details in their paintings (Indian ink in Gioka’s case and a variety of materials, including pastel, graphite and charcoal in Stupia’s).

A particular highlight of the exhibition was an introduction to the work of Lu Chao, a Chinese artist, still only in his mid-twenties, who graduated last year from the Royal College of Art’s MA course in Painting. Traditional Chinese ink drawing is a strong influence in his painting, although he uses oils, making precise and expressive brushstrokes.

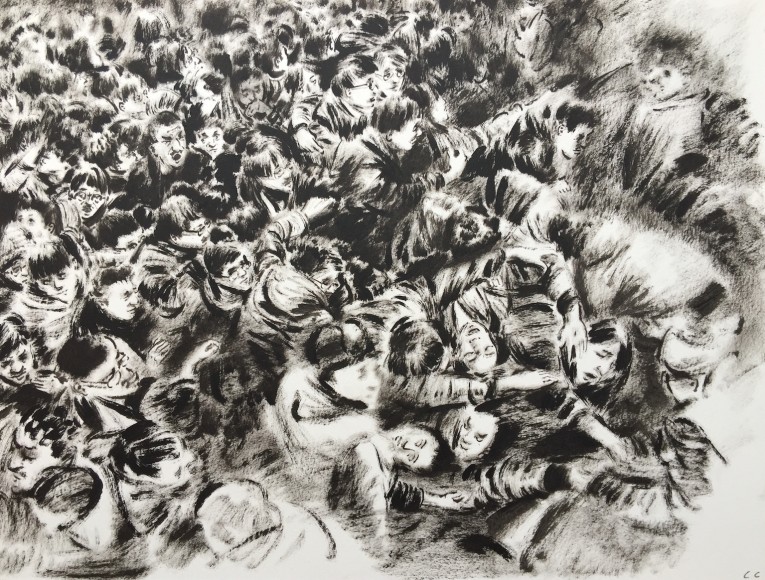

Five works by Chao are included in the exhibition, of which two are large oil paintings on canvas, while the others, still using oils, are on paper. The unifying subject matter is crowds of people; in China, much of daily urban life is lived among crowds. In two of the works, the crowds appear to be unwillingly but powerlessly corralled by some invisible force into cake-like shapes. In one, the crowd cake is under a glass cover; in another a number of them are shown on shelves in a cake shop, with spaces where slices have been cut out.

There are also some smaller works in oil on paper which look like they could be details from the larger ones. One just shows a hat on the ground, but in the context of the other images, one imagines it has been dropped or perhaps knocked off someone’s head. For this reason, that simple image of a hat creates great pathos. One cannot help but feel vast empathy for the hapless owner of that hat.

Chao’s interesting and original images express powerful ideas and ask important, and very contemporary, questions about the relationships between the individual and oppressive authority. It is extremely difficult to imagine such complex existential ideas being conveyed in the language of Conceptualism.

Throughout the great majority of the history of art, artists have responded eloquently to the questions posed by the human condition while valuing tradition and artistic skill and showing deep respect for the art form in which they work. Despite the rise of the conceptualists, many have continued to do so. This exhibition shows that there is still plenty of mileage in that approach.

Around Drawing is at Rosenfeld Porcini until 22 May 2015.