In her books Emily Carr depicts herself as a woman in exile and “contrary from the start”. The early twentieth-century photographs of her confirm an intransigent self-consciousness and stubborn gaze. Yet her paintings narrate a different truth: her absolute fusion with what she saw. She was equal to the subjects of her paintings; she was included in what was visible to her and her pictorial portraits of it.

Her first solo exhibition in the UK at the Dulwich Picture Gallery comes far too late, as the popular artist from Canada died 69 years ago; nevertheless, it is a clear display of Emily Carr’s essence. Her landscape canvases are revelations. Their meaning is absorbed by their visual representation and vice versa. They deny any distance between the painter’s inner space and her spatial surrounding, the territory of British Columbia.

The show paves the way for a light and at times illuminating wandering among her faraway achievements. Carr’s preferred topics for discussion sit next to each other in the gallery: mostly oils on papers or canvases of the Canadian rain forest, its trees and undergrowth are hung above masks, ritual objects and reproductions of First Nations’ culture arranged on tables. For most of her life, her desire for human proximity was exclusively addressed to groups of Indians living on the West Coast of Canada. The second room of the exhibition is dedicated to paintings of totems and traditional Indian emblems. Born in 1871 in the newly formed Canadian Confederation from English parents, Carr’s practice sought asylum in the Haida society.

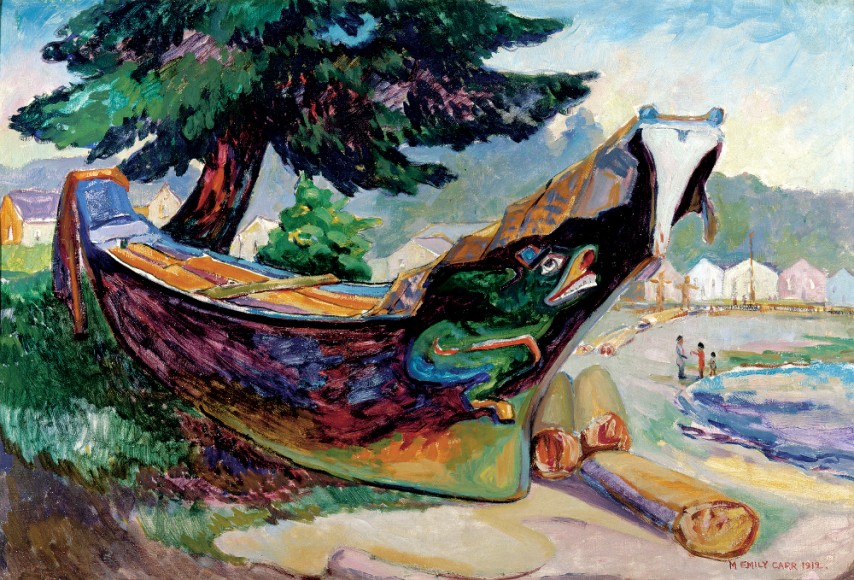

During her visit to the community of Ucluelet on the Vancouver Island, Carr received the name Klee Wyck, the Laughing One. Her playful side is shown buy her choice of a colorful palette and shimmering tones of blue and green. The 1912 painting Indian War Canoe is composed by fervent shades and evocative strokes that recall her encounter with post-impressionist and Fauvist techniques during her studies in France in 1910. Blunden Harbour from 1930 is placed in the same section of the exhibition and yet it conveys a divergent feeling with a more affecting effect: based on a earlier photograph, this canvas illuminates a dying culture. In this painting, Carr removed the native people of the photograph and let the totems of their village speak. Isolated in time and space, these monstrous statues loom out of the past into the present.

Rhythm, weight, space and force were the principles guiding Carr’s practice; today these qualities are joined by the fascination for her extraordinary story. The Dulwich Picture Gallery guarantees a thoughtful consideration of her work, without covering too many specialist details and thus avoiding the visitor feeling confused and disorientated, which frequently recurs in retrospectives. The show exhibits hints of beauty without satisfying the audience’s appetite, perhaps facilitated in this by Carr’s artistic activity.

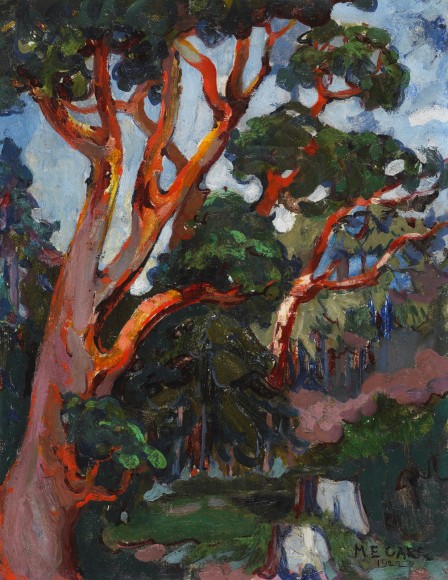

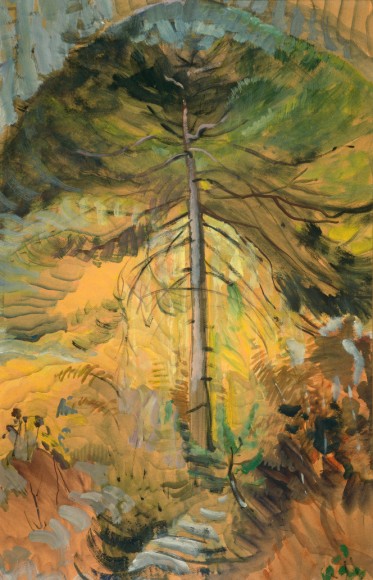

If one section is occupied by her timid experimentation with drawing, illustrated books and cubist compositions, a larger part of the exhibition is enriched by her studies on her land, woods and especially trees. These paintings are the worthwhile pinnacle of her career and of this retrospective. “I ought to stick to nature because I love trees better than people”, the sulky artist famously affirmed. Works such as Wood Interior, Indian Church and Tree embody Carr’s restless yearning for reality. She felt empathy towards nature, towards the forest which she preferred for its unadulterated pureness and bounty.

Her landscape subjects appear to be put in motion by a supernatural force, perhaps Carr’s own desire to get closer and join them in their uncontaminated oscillation. Windswept Trees from 1934 is an oil and gasoline work on paper magnificently overwhelmed by a spiral of emotions. A blow of air takes over the central tree and spins around the whole painting; influenced by Van Gogh shimmering objects, Carr developed his style further and made her strokes longer. The browns, greens and yellows are not colour but tangible movement. Carr’s images excel because their dynamic nature suggests the passage of time. Despite being fixed in a specific space and time, her work illuminates a sequence of moments: the Canadian artist’s windswept creations allow what came before and after them to be seen.

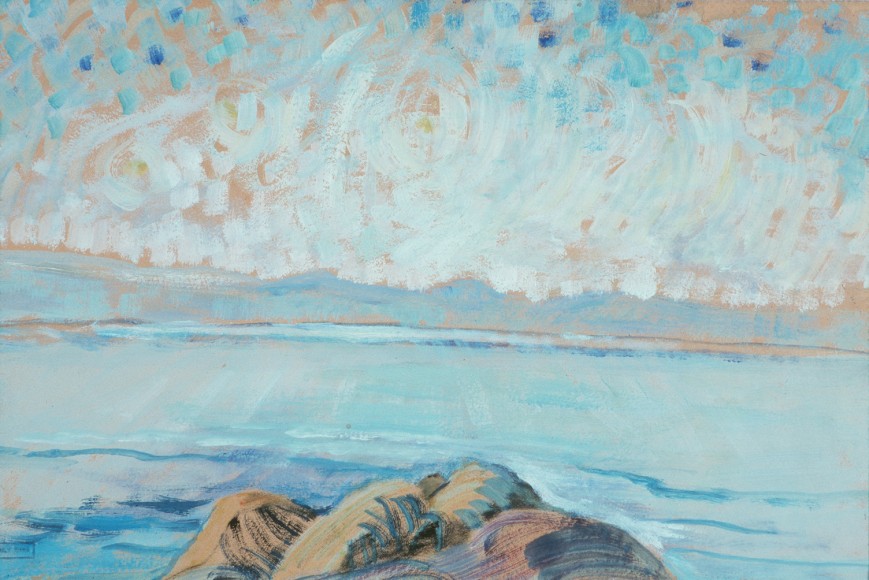

The Dulwich Picture Gallery concludes with Carr’s paintings of the sea and the sky. While paradoxically her maritime artworks are static and inanimate, her skyscapes encapsulate her movement away from the human landscape, towards the transcendence offered by silence, isolation and the harmony of the earth.

From the Forest to the Sea: Emily Carr in British Columbia is at the Dulwich Picture Gallery until the 15 March 2015.